‘First God, then food’

In November 1917 Swamiji was born into a Brahmin family in Karnataka, South India, and given the name Laxmi Narayan. He said little about his early life. A sannyasi, it is said, has no past and seldom mentions it. An exception to this was one of his earliest memories as a child age eight when there occurred a preview of what was to come in later years. He had been lying in bed half asleep and had seen a vision of a large red face with many arms which awoke a strange feeling in his heart. The vision stayed for a minute or two and disappeared. This was, he said, his first darshan of the eighteened-armed Goddess of Sapta Shringh he was destined to meet years later and recognize as his true mother.

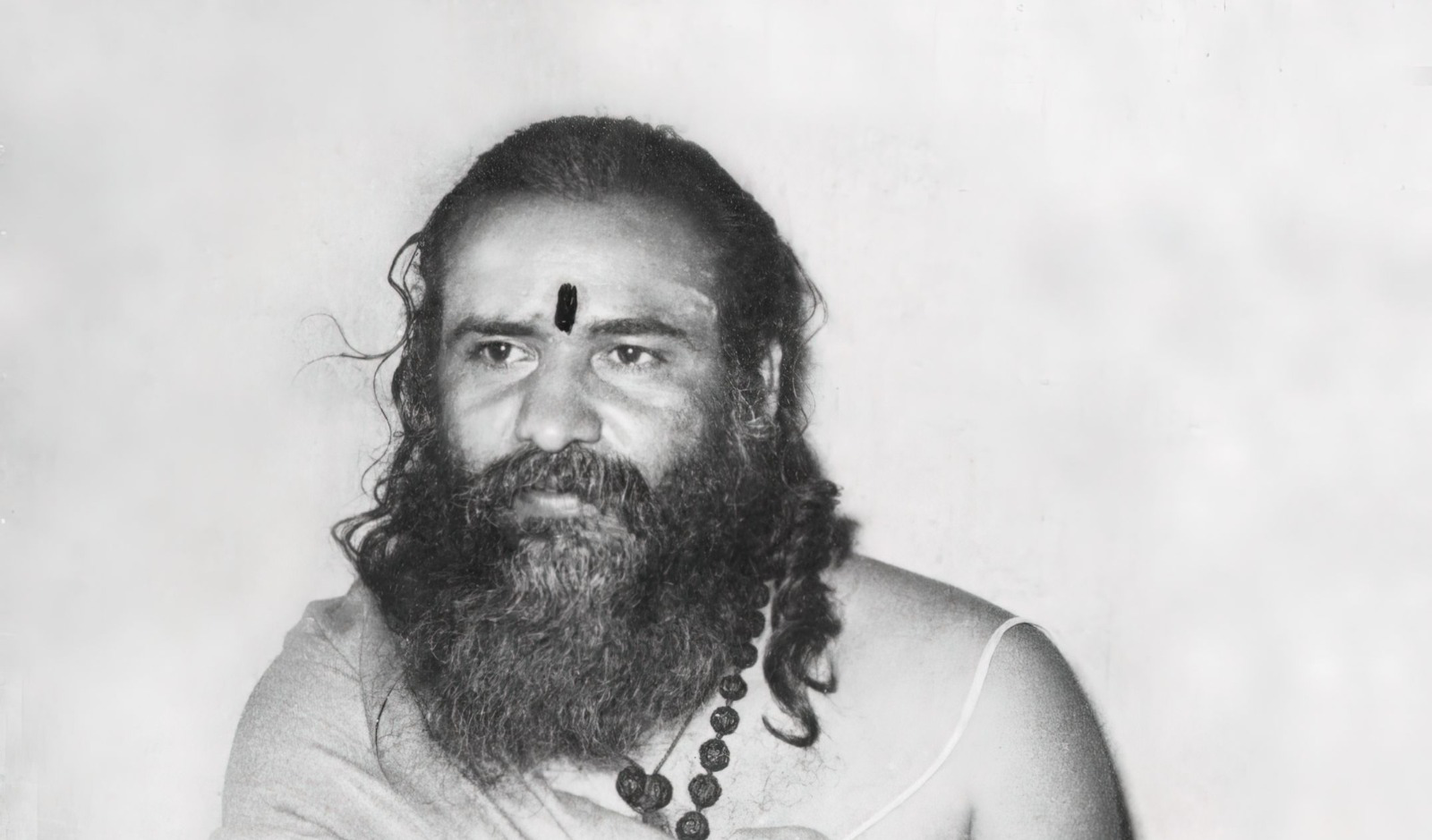

Early pictures of him show a handsome, finely proportioned young man with intense burning eyes and a fair complexion not usually associated with South India. We know that as a very young man he left home in Karnataka, South India, with a profound faith in Mahatma Gandhi and the Independence Movement, which he joined. Indeed, for a while he even enjoyed British hospitality in a political jail! Sometimes he remembered with a certain admiration the good food he and the other prisoners were served and how well they were treated.

However, after Independence in 1948, Laxmi Narayan gradually became disgusted with politics as he realized that, after all, a number of those who had taken part in the Independence Movement and had striven to dislodge British rule were only too human in their weaknesses and desire for the trappings, pomp, and power of those of whom they wished to be rid.

Disillusioned, he started wandering around India looking for that which lies beyond human limitation and weakness: God, the supreme fulfillment. Three times he completed entire circuits around India, one of them on foot, going as far north as Mount Kailas and Lake Manasaror in Tibet and south to Kanya Kumari. In his travels he met many different kinds of people and learned something from each of them. Sometimes he had money, often earned from his knowledge of astrology, and sometimes he had none, having to rely entirely on providence and the will of God. Often he went hungry, as his principle was never to ask for anything. This experience affected him profoundly and left him with a great love of feeding people, which culminated years later in founding an ashram dedicated to housing and feeding poor children.

One day in 1983 Kirin Narayan was researching her book based on Babaji's stories, Storytellers, Saints, and Scoundrels, and recorded Swamiji reminiscing about those early years. In the recording, we follow the young Laxmi Narayan passing through various life experiences and witness his gradual transformation. We see his idealistic allegiance to the Congress Party and willingness to die for the truth he believed in give way to a profound devotion to ultimate truth rather than secular ideology. In these reminiscences we catch a unique, fascinating, delightful insight into the mind, humor, heart, and world of the intense, guileless young man who was later to become Swami Prakashananda.

I was about eighteen when I left home. Why did I leave? My mother died when I was about ten, and one day I left home. At that time I was infatuated with the ideals of the Congress Party and thought of Gandhiji as a God, although I did not at that time revere God at all. Finally, I decided to set out to find out and explore for myself whether God was real or not and every day I used to spread my asan and meditate. I must have been in my early twenties at that time.

A relative of Swami Chidananda of the Shivananda ashram in Rishikesh met me and gave me a mantra. He advised me that if I were really interested in finding God, that I could go to one of three places where there were living masters who could guide me correctly. One was Hamsadev in Gujerat, one was Shivananda in Rishikesh and one was Nityananda in Vrajreshwari. These three gurus he told me about, but being independent I did not go to any of them. I took a train to Poona. From Poona I tried to get a ticket to Kashi (Banaras). At Kalyan I found I did not have enough money for a ticket all the way to Banaras, so I pawned my watch for about ten rupees and bought the ticket. So there I was on my way to Kashi!

I was warned before I arrived in Kashi that the priests there will rob you for four annas; their reputation was that bad. I found a place to sleep but food became a problem as I was a strict Brahmin. Also, I knew very little Hindi, only what I had learned during my association with the Congress Party. This must have been about 1939 or 1940. Everything was very cheap in India in those days but I could not eat just anywhere because I would not eat without being certain of the purity of the food, so I went hungry.

I met a Brahmin who said he would take me everywhere for one anna. That seemed reasonable enough so I entered into contract with him. We started out to see Banaras. He took me around saying 'Worship here for your mother, honor this image,' and so on until fairly soon I had virtually no money. I was stranded and penniless. A sadhu came up and offered to help me. He was wearing saffron (the color worn by a renunciant). I distrusted all Sadhus because, being a staunch member of the Congress, I was convinced that all those who wear saffron were thieves or cheats. But he persisted in calling me and when I told him to go, he wouldn't leave me. After I had been arguing with him for over a half hour, a Brahmachari came up wearing a white cloth. I preferred the look of him in his clean white clothing.

'What is your guru's name?' I asked.

Satyanarayana Maharaj,' he answered. His own name was Shankar Ananda Bharati. He said, 'Come along and I will take you to my guru.'

He took me there and his guru asked who I was and where I had come from. 'I am here to become your disciple,' I answered. 'Tell me what a disciple does. How do I become a disciple?'

He answered, “There are three ways. We can arrange for you to study English, and to study Sanscrit, or to become a sanyassi. You can choose whichever direction appeals to you. You decide which path you want and then you take it.'

This won't do for me, I thought. “Just give me a mantra,' I told him. 'I am not going to shave my head, and I am not going to wear saffron. Just give me a place to stay, not even food or water. Give me a place and I will sit there without food or water until I see God. Can you give me a mantra by which I can accomplish that? I have come all the way to Kashi to see God. If I do your work will I see God? If I am just going to work I might as well work for wages elsewhere.'

'No,' he said, “it cannot be like that. Without shaving your head and without doing our work, we cannot keep you here.'

Then I asked him, 'Have you seen God yourself?' 'No,' he answered truthfully.

'So,'I said, 'if you have not seen God yourself, how are you going to show me?'

I left. I still had about a rupee, which saw me to Allahabad. I traveled with a Madrasi whom I had met. We stayed in a dharamsala and in the morning after we had tea we decided to sell our gold earrings. People kept looking at them, either out of curiosity or because they were planning to steal them, we couldn't tell which, so we thought we should rid ourselves of those dangerous controversial objects. Then we went straight to the Nehru residence. I thought if I was not going to find God, I might as well stay with the Congress Movement. But that day Chiang Kai Shek had come to India and Nehru had gone to Delhi to meet him.

I met a lot of the great Congress leaders who were staying there, Nariman, Munshi, I saw them all. I said I would like to stay there.

I was skilled at spinning and wore only cloth woven from the cotton I had spun for myself. I demonstrated how well I could spin and told them about weaving centers I had organized in the South. I could take out a ninety count thread, which is very fine.

'Stay,' they said, as they were pleased, and meet Nehru when he returns tonight.'

But after an hour I felt like leaving, so I went to the station.

Hard Times

Then followed a period of wandering in which the young Laxmi Narayan passed through many life experiences. Hunger, destitution, and even arrest by the British were just a few of the experiences and they served to temper his character like iron in a furnace. He met saints and sinners and learned something from them all.

Finally, in Darwar, I took a job in a shop. When I have enough money, I thought, I will go on. I went into the shop and told the man I would work for my food and eight annas a day until I had enough money to go on. I had no idea where I would go. He agreed, so I worked for eighteen days until I had the money for a ticket to Bangalore. In Bangalore I did the same thing, working until I had money to go to Sailam. In Sailam I ran out of money and could not find work, so I left there on foot eating the leaves from tamarind trees with only water to drink.

Sometimes someone gave me something, sometimes not. I was disappointed in the ideals of the Congress and I had not found God. I used to stay five or six days in one place and then move on.

Near Dindugal there is a temple of the Goddess at Maddiguddi up on a high rock where I slept. At night ghosts and spirits hold dominion there and they manifested all around me, but I was completely unafraid.

In the morning I started off to Madurai. The road that leads from Dindugal to Madurai is very beautiful, and huge old tamarind trees shade the road on either side. About five miles outside Madurai I stopped to drink water at a small tank. Approaching the well I tucked my lungi and held out my hand to catch the water that was pouring out. As I tucked up the lungi, the fabric split from behind. My lungi tore so I could not wear it properly and I had no other, only a long shirt. My lungi had split exactly in half. I tied one half around my waist but it was not long enough to show beneath my shirt. To avoid looking naked, I removed my shirt, bundled it up under my arm, and threw the other half of the lungi over my shoulder. My only other possession was an old cigarette tin which I used for water. Carrying only that and dressed in this manner, I entered the great city of Madurai.

Meeting with a Jnani in Madurai

Madurai is a large city centered around the extensive ancient temple of the Goddess Meenakshi. Just the space enclosed in the Nandi Mandap of that temple can sleep over four thousand people. Near the temple the government has provided bathrooms for the public that are as well and beautifully built as temples. I went into one and bathed and washed those bits of cloth of mine.

I walked back to the center of the town, to the temple, and sat in the square around the sacred compound near the temple of Meenakshi. There is a custom there that before opening their shops in the morning many of the shopkeepers give charity in the form of chits, coupons that can be exchanged for a meal or snack. I was sitting there watching fifty or sixty sadhus about a hundred feet away from me scramble for the six meal tickets that one merchant was distributing. I sat at a distance watching the play, seeing those sadhus in saffron push and grab and shout, laughing to myself with my hand under my chin and thinking, 'look what the world does for food.'

An old sadhu, a mahatma, came up beside me and said, 'I'll get you a coupon.'

'For what?' I asked.

‘For food,' he said.

'I have no need of that.'

'Why?' he asked, 'Don't you eat?'

"Of course I eat, how could I have gotten so big without food?' I answered arrogantly. But I don't need food now. I am not eating.'

'Why?' he asked.

'First I want to see God, then I'll eat.' He asked me where I had been and I answered 'Kashi bashi, I have been all around.'

‘Hasn't anyone been able to show you God?' he asked. 'No,' I said. 'Why? There are good mahatmas in Kashi.'

‘No,' I answered. 'They were all sinners. Everyone was out to rob me.'

I told him a few of the incidents from my experience. After a time, he said, 'Well, what no one has shown you, I will show you. I will show you so that you will be able to eat again. Now first let us eat.'

'No.' I was adamant. “First God and then food.'

Actually I had been practicing meditation all this time and had seen a star, a brilliant point of light. Patiently, the old mahatma began to question me.

'Is the seed in the tree or the tree in the seed?'

I was silent.

'Answer me. Is the seed in the tree or not?'

I could find no answer so he went on to explain.

'In all trees there are seeds. Without seed no tree comes into being. Where is the seed? It is potential within each tree. If the tree is not watered it will die. How long will a sapling live without water? In a few days it will die and when it is dead there is neither tree nor seed. If one wants the fruit, the seed, one must protect and nourish the tree. At the proper time, in the appointed season, the tree will bear fruit, but never without having been protected and cared for. In this same manner, God is potential within you. If you want to realize Him, you must protect and nourish your body and you will have to continuously repeat the mantra you receive from a guru. Then from within, God will become pleased and His pleasure will manifest in you.'

In this manner he gave me understanding and then there in Madurai, in the temple of Meenakshi, he gave the mantra to me. For three months we traveled together from there, visiting all the holy places in the southern tip of India, such as Rameshwaram, Kanya Kumari, and so on.

Once in Rameshwaram we were sitting outside a house under a tree. The people were known to us there and in the most friendly and hospitable manner had prepared food for us. We had all eaten and the banana leaves from which we had all eaten had been thrown out onto the rubbish heap. Although no food was left on the leaves, four dogs fought over the rubbish for their share. Then a beggar came up, and beating off the dogs, picked up a leaf and began to lick it.

"See,' said my Babaji, 'truth and falsehood, rules and cleanliness. The soul makes no distinction when the body is hungry. In times of hunger all discrimination falls away. Understanding this, in the future you should give food. It is with this understanding that you should feed others. Understand that all souls are your own. All living beings experience hunger and require nourishment. At some time in the future you should provide this. God sits in the heart of all beings. Whoever you feed, that offering reaches God. Give to the hungry and the poor without distinction of caste or custom.'11

In this manner for three months he used each sight to teach me as we walked on pilgrimage. In some places people called us and honored us, fed us and gave us gifts, and in other places not, but everywhere we moved in joy. After three months we reached Palni and there he instructed me.

‘Now you must find work. You must not waste your life begging. Continue to remember God and you will find Him.'

At first I was not able to find employment because I was not well-dressed or shaved, so he gave me money for a shave and a new dhoti and then I was able to find a job in a shop. What wages? Three rupees. What work? Carrying water. It was all right. Following the guru's orders, I continued to serve. However, after two or three months, I became ill with blood dysentery. I had to go forty or fifty times a day. My employer gave me some medicines but they were not effective. He was unwilling to spare me from work but after some time I was physically unable to work. I was too weak even to reach the bathroom and so he took pity on me and gave me a place to rest. I became seriously ill so they took me to a hospital thinking I was about to die. The doctor there turned out to be a caste fellow of mine. He gave me excellent medical treatment, kept me in a special ward and paid attention to my case. He noted my name and found out where my home was and after contacting my family and receiving some news from my home, he took even better care of me. After eighteen days, when I was well enough to leave, they came and took me back home.

Satyagraha and Prison

After some days at home, I left for Mysore where the Congress movement was active. I got back into the Independence movement and was friends with many of the leaders. Every day orders were given for satyagraha and every day there were reports of activity, but it was untrue. No one ever really went because they were being beaten on the way and they were all scared.

Good,' I said, 'I will go. You can only die once, not over and over.'

So at a mass meeting, in front of a crowd of four thousand people, I volunteered and others joined me. Nine of us gave our names and in front of all those people our names were announced. The leaders all came and argued with me.

'We cannot allow you to go. This is Mysore and we should go first or they will honor you and respect you more than us. Do you have funds for your expenses?'

'I have no need of money,' I replied. 'We will take alms as we go and accomplish our satyagraha like that with the support of the people on the way. I don't require your permission and I don't require your funds and I don't need your support. I am going right ahead with my plans.'

Hearing this, the Congress president of that area came and joined our party. Due to his leadership there were thirty-two of us when we set out.

Our group moved on to the next zilla where four or five people who were important and well-known in that place courted arrest. At night, if you gave a speech, you were arrested. The rest of us would move ahead toward Mysore. Each day another batch of satyagris would move through the area. I took one man and went ahead to prepare for our party. All but the two of us were arrested. We waited and then caught a ride back and questioned the police, who informed us that we would also be arrested. They took us themselves to the place where we were to be arrested. There was a big riot going on there and the whole town of forty or fifty thousand was out. Later, as we were being taken away, my father and brother came and tried to take me home. I refused, saying that I would not return home until my country was free.

The police officers in that area were all friends of my family's. They refused to arrest me.

'Do what you like,' they said, 'we will not arrest you. No one in this district will arrest you unless you do something really illegal like cutting down a sandalwood tree.'

The next day nine of us collected nine axes and took out a procession to advertise our intention of cutting down some government sandalwood trees. We didn't actually cut down any trees, we just said we were going to, but still no one came forward to arrest us. When our procession had gotten half a mile beyond the town we flagged down a car. We got a ride to another town about thirty miles ahead where three people had been shot and there was a curfew in force. Strict rules had been passed and the police had been ordered not even to give water to the Congress prisoners.

While we were in that town we just took off our Congress hats. Only by our hats could we be identified as Congress members. We made full inquiries, as this was another district, and found out that they were taking people two miles outside town and beating them up.

Two of the other men with me heard this and fled, saying, ‘We don't want to come along. We don't want to be beaten!’

The next day we let it be known that we planned to leave for Mysore at four o'clock by a particular route. At three we started out by another route. We said four but we left at three. Just outside the town we stopped a car and rode in it. The police were stopping cars and looking for us. At Shri Rangapatam there was a curfew and the motor bridge over the Kaveri River was blocked by police at both ends. All the vehicles from all over Mysore were being checked thoroughly and all suspicious characters were being beaten up on the spot. Because of this, we stopped at a village at about eleven at night. A man came and directed us to a place where we would be fed by the Congress volunteers of that area. It rained heavily all that day. We sat there and thought about finding a way across the river. About three hundred people trying to cross in boats had been intercepted. What was to be done?

'How will you go?' we were asked. “The police are beating everybody up. You had better turn back.'

But Mysore was only fourteen miles away.

If I die.' I said, 'I die. When you get born, you are bound to die sometime. I am going to Mysore.'

When we got about half a mile down the road, a police car drew up next to us. The inspector in that car was called Mustafa. I still remember his name.

'Where are you people going?' he asked. ‘Mysore,' I said. Arrest them all,' he commanded.

So they arrested us all. One of our party was the son of an influential millionaire. They asked him where he was going and he said, 'To my wedding.'

They could see by his dress that he was lying and beat him over the head with a stick. The blow broke his skin and he began to bleed.

'You demons! You have made me bleed!' The rich man's son was indignant.

Hearing this the police began to laugh and with the laughter their anger was spent. They took us off to Shri Rangapatam and detained us. The first day they tried to reason with us. We refused to listen and remained in the jail. So they detained us. We organized ourselves and appointed a spokesman for the detainees. We were not properly fed so we organized a one-day fast for better food. As a result, some of us were transferred to the jail in Bangalore where two thousand people were already being held, of whom nine hundred were detainees. Soon a separate camp was set up at Whitefields where we were all cared for as first class prisoners. We were still there when Independence was achieved and we were released. Many of my fellow prisoners later became important politicians in the Congress party and I could have done the same.

Further Wandering

All this time I was still searching for God. My wanderings took me to Goa where I spent several years. There I was not involved in politics but in religion. I became known as a soothsayer and an astrologer by telling a truth to someone who would then bring his friends. I earned a lot and so every few months I would set out pilgrimage from there. I earned so much that after a year I began to give predictions free. In that manner I spent over two years there and during that time, buying my tickets, I traveled all over India from the Himalayas to Kanya Kumari, the southern tip of India.

I will relate just one incident—so many things happened during those years and on my travels—to illustrate my powers at that time. There was a girl of about sixteen who was dying. The doctors could do nothing for her. Her mouth could not be forced open and she was near death. Her family came to seek my advice. I saw that something from outside was affecting her.

'I will do what I can,'I told them, 'bring me a lemon. I will know with one lemon if she can survive.'

I took that lemon and prayed. I prayed to all the deities and saints of whom I had ever heard. Nityananda's name was a part of my prayers even at that time. I did all this just as it came into my head spontaneously.

I cut the lemon and showed them how to force it into her mouth and kept the other half for the next day. But by the next day she had come round and asked for tea. No other medicines, just a lemon and the name of God. I am describing just one miracle but my reputation was based on many. They called me a man of God!

From Goa, Laxmi Narayan went to spend some time at Gangapur, a spot sacred to Dattatreya and it was here that he first heard about a mountain sacred to the Divine Mother. Its name was Sapta Shringh and an extraordinary destiny awaited him there which was to influence the lives of many people as well as completely transform him. One day in 1953 he came to the little-known mountain of Sapta Shringh about 40 miles north of Nasik in Maharashtra and his wandering ceased forever.

1 Author's note: We can judge the impression this teaching had on the young Laxmi Narayan in view of his later commitment to feeding others on a large scale at Sapta Shringh.